It is really very good, though. It’s very meditative. Calming. It’s possibly exactly what you need right now.

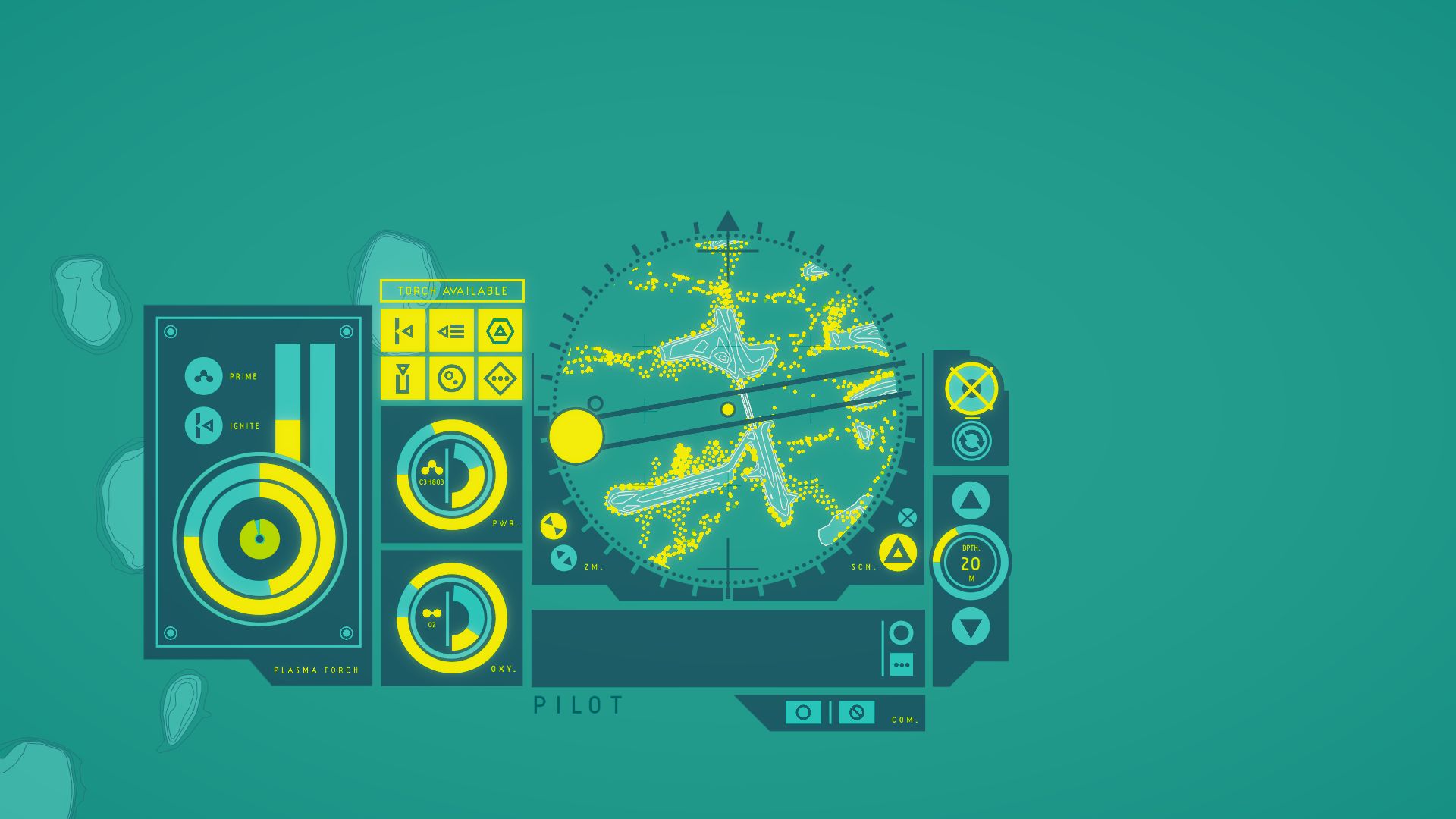

Because you are just a sentience inside a fancy science tuxedo, and can only answer any infrequent questions Ellery asks you with a yes or no, you view the world of In Other Waters as a user interface. Your control of the suit includes navigating between different set way-points, managing the power and oxygen levels, and eventually using tools - a specimen collector, a jet propulsion system and a blowtorch - all through the elegant suit display. Click to select a way-point, or open your specimen storage, or the panel to connect to call for extraction, everything simple but clear, and no more complicated than it needs to be. But more importantly, you never really see the ocean you’re exploring. It’s a topographical map of the area, the immediate surroundings rendered in scant more detail by your scanner pinging off points of interest. Except you do see it. Ellery is a dutiful and fastidious scientist, and she describes everything in wonderful and poetic detail. So what you encounter as yellow dots clustered together, she describes as forests of tall fungi that she calls “reef stalks”. On the eastern side of the map you see strings of different yellow dots, and Ellery tells you they’re delicate silk strands between tall pillars of rock. And the little dots moving, hopping along those strings? They’re feathery creatures she calls gardeners.

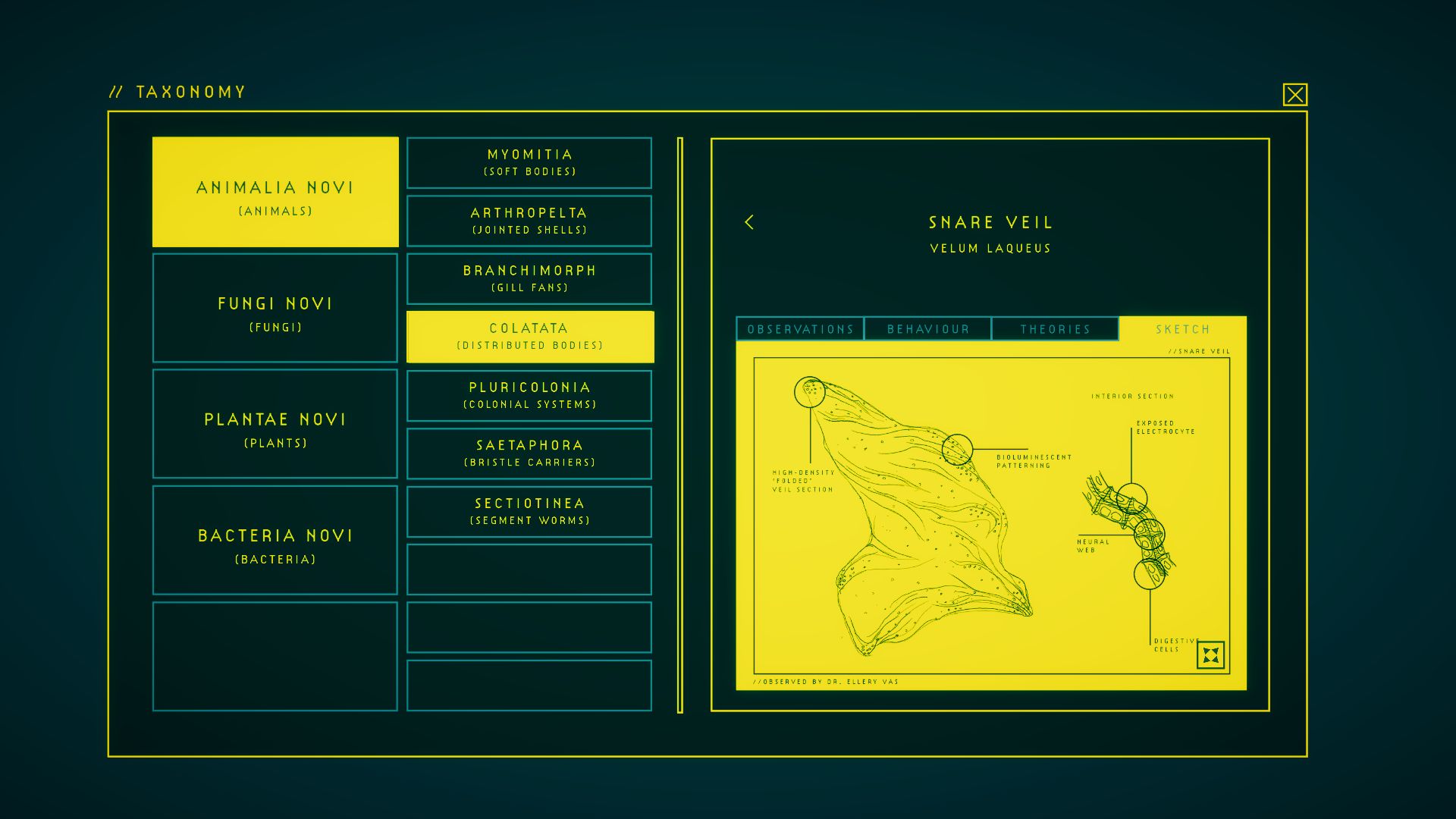

Ellery even describes the way-points you travel to as you scan and discover them, so that In Other Waters becomes almost like reading a dreamy, science-y novel. The bumps and whorls of the ocean floor rise up in your mind’s eye, becoming populated by the skittering symbiotic sea creatures as Ellery makes more observations about them. If you make the effort to collect the samples she needs, and scan them back at the surface-level staging base, you’re rewarded by an improved taxonomy. Eventually, if you complete the study of a creature or plant, Ellery will even include a sketch. Only a little one, though. Only a stolen glimpse, so your imagination isn’t totally ruined. In Other Waters is written with the same clarity and brevity as if someone had shown you a photograph, which is what makes the UI interface possible - preferable, even - rather than frustrating. The controls are streamlined, everything makes sense, and you actually get to be an efficient and competent diving suit.

At the same time, of course, you’re tracking a story. Ellery works for a science megacorp, which sends her to planets only to confirm that they’re devoid of life so they can be strip mined for mineral resources. This planet, then, is something of a coup, and she’s here a bit off book, at the behest of a scientist friend who was here previously. In classic show-don’t-tell style, Ellery hints at how close their relationship was, without delivering a blast of hackneyed exposition that ruins everything. You track previous discoveries, eventually finding a toxic algae bloom to the east and some mysterious ruins in the deep dark waters to the north. You overtake those discoveries. You do some light puzzling; you research the effects of different samples and find out that you can, for example, use “shrillsacs” to clear forests of reef stalks that block your path, or colonies of creatures to clear the toxic algae bloom to let you breathe again. You help Ellery make some significant decisions, and she begins to trust you. There is, naturally, a terrible secret to uncover, which you can do in about four hours. But In Other Waters remains calming and lovely throughout because the terrible secret already happened decades ago, and the planet survived. Life adapted, changed, and eventually thrived again. So there’s no burden on your shoulders, really. Oh, there is the always increasing burden of being human, the greedy, thoughtless, uppity ape that ruins everything. But what else is new? You can’t change the past in In Other Waters, you can just be a witness to it. And a witness to everything else!

Because this little world, this pocket eco-system, is really great. And it all makes sense, too, and crucially makes sense with reference to my dim understandings of life on earth. The reef stalks are fungi forming interconnected colonies with root systems underground, which I am happy to accept on the basis that earth ‘shrooms do the same thing, and are likewise deeply unknowable. The deeper ocean floor has deep brine pools, which we know about because we saw them on Blue Planet II! And who should live there but little whiskery crab creatures who grow bubbles of breathable gasses on their back, as a natural diving kit so they can explore the pools for food. You get to be methodical. Curious. Work through all the different species you need to research. Log all the specimens you need. Update all the taxonomies until you know everything you can about this world. You can order it all, and order your mind. You can imagine Ellery’s careful steps. You listen to the deep, slow breath of the ocean rolling overhead and around you. Ah. Lovely. Disclosure: In Other Waters is largely the work of Gareth Damian Martin, who wrote for us one time. Alice didn’t know that when reviewing the game and, really, who hasn’t written for us at this point.