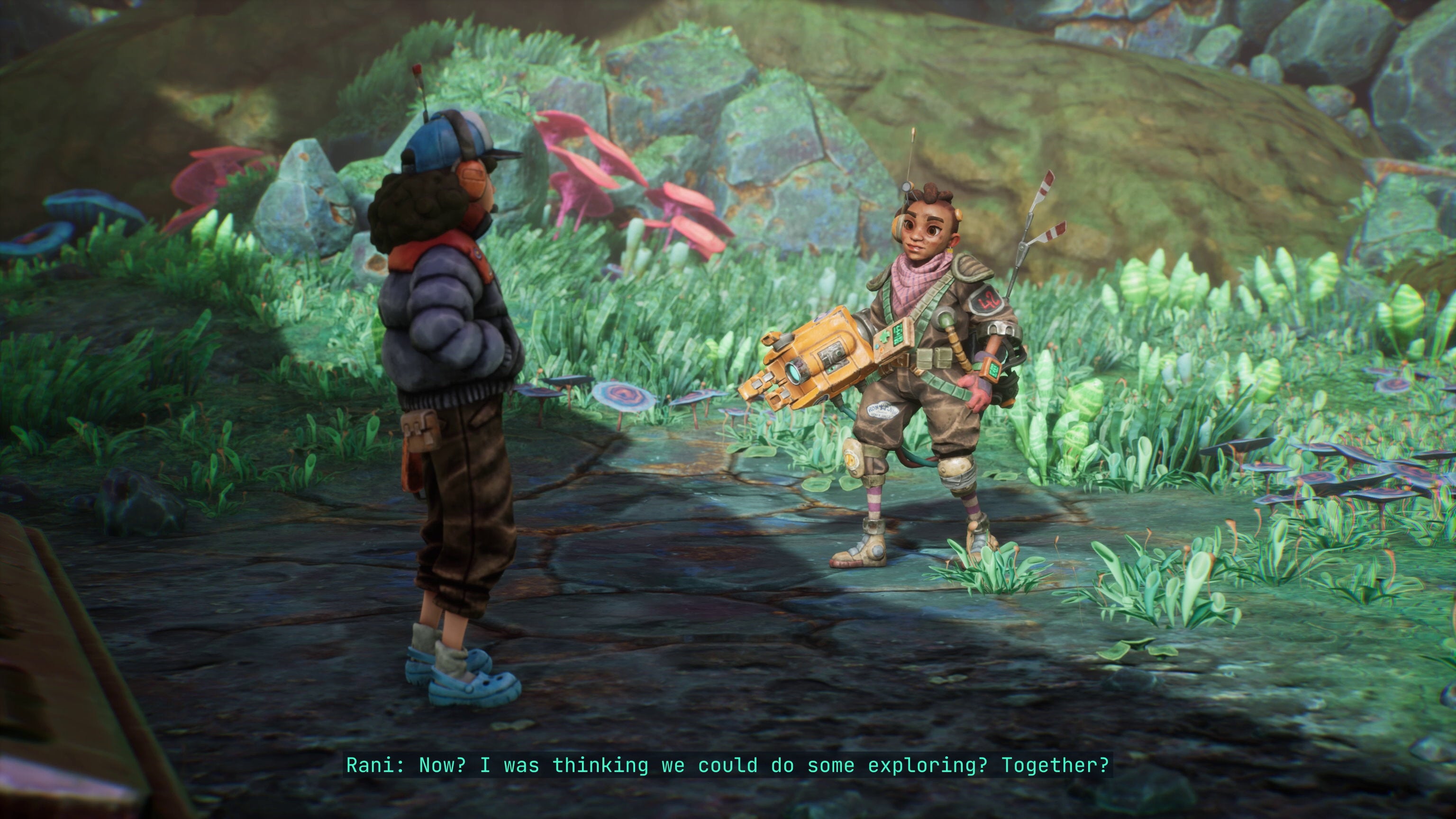

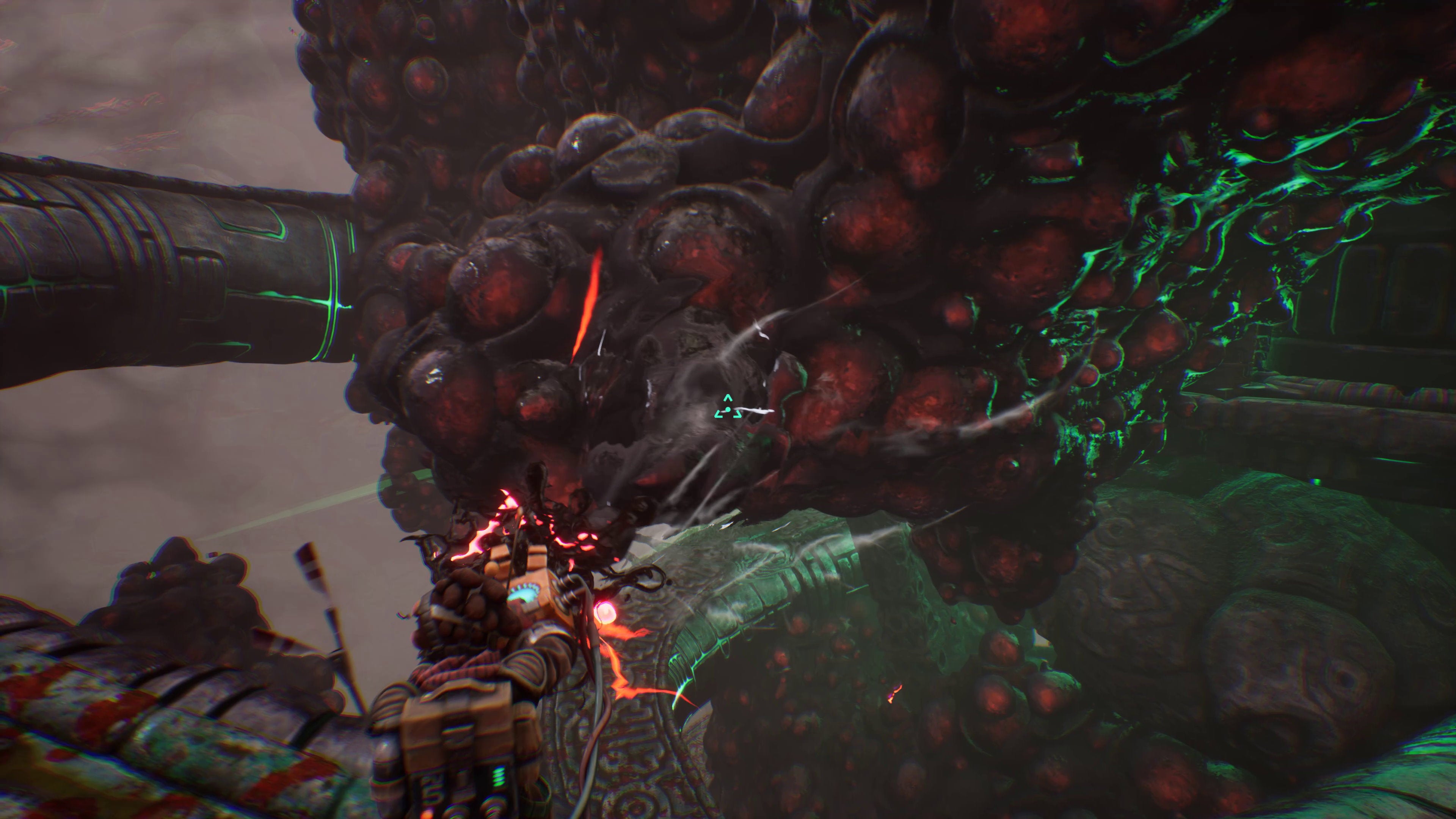

“We’d only ever done 2D games in our own in-house tech,” director Ulf Hartelius says. “The main spark for The Gunk came from working on different prototypes in Unreal and getting up to date with the engine and working in 3D. Some of our early prototypes were SteamWorld, but The Gunk’s prototype wasn’t, which was also very intentional from our end. Creatively we wanted a break from the SteamWorld games, and that world to recharge our batteries and do something else and be allowed to do other things. “For various reasons, none of these prototypes really took shape, but at one point we stepped back and looked at the last one we’d been doing. We figured out it was doing way too much, but we liked one aspect of it. It was a game with a lot of different abilities, but it had a blowing and sucking wind mechanic - that was pretty cool. We could probably do something if we did just focused on that, so we ripped everything else away and just had this little tiny thing that was a top-down jungle environment made from like one mesh, and we filled it with mist as little balls. We made it so you could just suck up these balls, and that way you would reveal this jungle environment as you were exploring and picking up coins.” The prototype soon gathered speed as Hartelius and his team started to pass it round the office, the bulk of which was still working on polishing up their deck-building RPG SteamWorld Quest at the time. “It really triggered that itch for exploration, and everyone just really liked it,” says Hartelius. Realising they’d struck on a good idea here, Hartelius then started asking a lot of questions. “This mist, what could that be?” he muses. “And is it covering the entire level or just sections? Does anything happen when you remove it? Or is it just to see what’s underneath? Does it affect the environment? If it’s covering the environment and removing it changes the level geometry, then it must be some kind of corrupting influence, some kind of pollution… A lot of things like this came very naturally to us.” Around the same time, the team were also starting to peel back the layers of The Gunk’s underlying story. They knew they wanted a female lead driving the story forward, and that she’d have what Hartelius describes as “a scrappy kind of enterprise doing odd jobs for big corps” with her best mate. “I’m really fond of the radio banter that we have in the game,” he continues. “I love that ongoing, not cutscene-stopping narrative kind of storytelling, and it suited itself very well to that.” Before Hartelius could go any further, though, there was one final question that needed answering: “We had a lot of bits and pieces, but then it’s how do we make a game out of it? And that took a long time, and a lot of experimentation. We tried going too deep down various avenues. At one point, it was very open world-ish, but that had its challenges, not to mention how you interacted with the mist, which of course became the Gunk.” It’s perhaps a little ironic that the black, gooey substance that would go on to give the game its name would end up being the most difficult part to nail down, but it presented the team with a lot of real world technical challenges. “Not only was Unreal and 3D completely new to us,” Hartelius recalls, “but it was also a question of, ‘We have this dynamically shaped thing that’s covering huge areas of the environment… what kind of tech do we even use for that?’” As their ambitions grew, Image & Form tried various solutions, but Hartelius also admits that “every time we changed that tech, we also had a scrap a lot of stuff, of course, because a lot of previous work was incompatible. As I said earlier, the Gunk was just this mist that existed as balls. We just placed 1000 black balls in the environment that you sucked up. And it looked really bad, and it was really bad for performance, so that was never an option, but we built our first levels using that.” Gradually, those Gunks balls became the more amorphous kind of Gunk you see in the game today, but various technical limitations still prevented them from making a Gunk that would allow them to “get it up on the walls, up on the ceiling, [… and let] players be able to dig into it,” says Hartelius. “We wanted to make these vertical levels and not be constrained by being trapped on the floor with a height map. That’s how we eventually landed on our final technique.” After two years of pre-production development, the team had finally done it, although even Hartelius admits that the 3D Gunk they settled on in the spring of 2021 was “still nowhere near to the final shape it has now” in the finished game. “It was very much a matter of give and take,” he continues. “With this technique, we can get it in the ceilings and do all these cool shapes with it, we can make it boil and bubble, and blend with itself. It gave us a lot, but we also had to make a number of concessions with that, from a technical standpoint. Before that, when we had this height map-based tech, we experimented with lots of different types of Gunk, but our ambition were too big. There was going to be lava variant, a snow variant, a fog variant and so on. It was a long process. It’s kind of wonky, but it’s pretty fun taking that all the way to something you can actually ship. Eventually, though, we decided to focus on the default Gunk. That’s going to be good and juicy, and we’re going to build on that as far as we can.” With the tech side now in place, the team still had to finish answering the ‘how to make a game of it?’ question. “Just from a level design perspective, we had this thing that was concealing something underneath it, but how do we entice the player to remove it to reveal something they can’t see?” Hartelius says. “Can I make it so there’s an active choice about which part of the Gunk I’m going to attack first? Does that matter? In the end, we made it so it didn’t really matter, you have to absorb it all, partly for that reason, because it was so difficult to get players to make an informed choice. You can’t really do that when you don’t know.” Indeed, Hartelius says they “hit a lot of walls” trying to blend everything together. “Coming from the 2D games, especially SteamWorld Heist and Quest, which are turn-based games, they kind of have it easy, in some sense, so we looked more to the SteamWorld Dig games. A lot of the movement stuff is taken and adapted directly from them, because even though this isn’t really a platformer, we still wanted the platforming to be, well, maybe not as good as the Dig games, but we still wanted fairly tight platforming controls, because there’s nothing that takes me out of an experience more than bad platforming!” A tension was beginning to emerge. For Hartelius, The Gunk “was always about exploring this environment, removing the Gunk and revealing what’s underneath and triggering that new second layer of gameplay.” But when they started bringing in play testers, not all of them were on the same page. “It seemed like a pretty clear split between those who really get it and really enjoy being in this world, versus those that want some kind of deeper gaming challenge.” In fact, Hartelius himself concedes that The Gunk probably “has better controls than it should have, given how easy the platforming actually is in the game,” and he tells me how some reviews ended up criticising the game for not having more advanced platforming sections. “Someone even thought it had good enough controls for it,” he says, “and I agree! But we also learned doing this project that it takes a long time to make an area of this game, particularly with all its lush geometry and environments.” In the end, the team moved forward with their original vision, pushing aside any lingering concerns they’d received during those pre-release playtests. “We’ve always been afraid that maybe that segment of people who like the atmospheric exploration was really small,” says Hartelius. “But it doesn’t seem like it. It seems like there are a lot of people who really like this type of game and experience. I would love it if we had had the opportunity to give the ones seeking more depth in the gameplay something as well, and to get the Gunk to evolve more in the game, but we kind of ran out of time eventually.” Despite its various setbacks, there was one part of the game that resonated with everyone, and that was the environmental themes running throughout Rani and Becks’ entire adventure. Indeed, in many ways The Gunk builds on what Image & Form have been doing in the SteamWorld games for years, many of which take place on a ravaged, Earth-like planet where some kind of climate crisis has already happened. But The Gunk takes it a step further. Not only are there references to Rani’s home world having already been ruined, but your primary purpose in the game is to help her clean up this new planet to restore its balance - and unlike a certain other post-apocalyptic game that came out recently that just happened to coincide with everyone going into lockdown, the inclusion of these themes “was very meaningful and deliberate from the get-go,” says Hartelius. “At our launch party, I had this little speech where I recounted how we came to be where we are, and when I looked it up, I realised that we started with The Gunk like a month before Greta Thunberg’s first protest. It’s very much in that same context. But personally, I’d also been becoming more aware in the years leading up to that and I’d also been growing kind of impatient about the SteamWorld games, because, as good as they are - and I’m 100% super proud of them! - they don’t really have all that much real world meaning. I really wanted to make a game that could, at least marginally, affect people and help them see the world in some kind of new lens, or just make them slightly more aware of things and question things like the environmental impact we’re having on the Earth. I figured if I can do that, then this game is so much more meaningful.” The Gunk is out now on Steam for £20/€25/$25, and you can also find it on the Microsoft Store and Xbox Game Pass. You can also read our review of The Gunk right here.